LAND AND WATER EXTRA

Women in the War Edition, April 1919

*****

The April 1919 edition of 'Land and Water Extra' was devoted to a summary of women's work during the Great War. Each of the women's services was given space for a summing-up account of their duties and experiences during wartime. Among them were some that are not well reported elsewhere and it seems worthwhile to repeat them here. One or two appear to have been written by men who were not convinced that women had much of a part to play, but they give an interesting perspective on attitudes to women at that time.

1. Women in the War Office

2. The Blue Triangle - The Young Women's Christian Association

3. Women's Forage Corps

4. Women's Forestry Service

*****

1. WOMEN IN THE WAR OFFICE

The War Office policy in regard to women workers has been that of encouragement and sympathy; where promotion has been possible the women have had the benefit and the general consensus of opinion has been that they have justified the confidence that the authorities have placed in them.

There are four grades of women clerks, excluding girls – Junior Administrative Assistants and Grades I, II and III. Brushing lightly over the latter two grades in which are included routine workers and supervisors, and whose salaries are as follows: 37s. 6d. for a working week of 44 hours, rising by annual increments of 2/- to 43s. 6d. in the case of Grade III, and 45/-, rising by annual increments of 2s. 6d. to 52s. 6d. in the case of Grade II, we come to the Junior Administrative Assistants and Grade I Clerks, whose work is quite removed from the above categories.

The Junior Administrative Assistants are, in the majority of cases, women graduates, and where this is not the case have some technical qualification which renders them peculiarly fitted for the work which they have to perform. The work which they have been called upon to do has been that which would, in normal times, have been given to either a junior Higher Division Clerk or to that of a senior Second Division one, though it is only fair to say that in many cases the women have had to create the posts which they at present fill because such posts were not thought of prior to the war. The outstanding feature throughout their work is an attention to detail and keen interest; they are adaptable and quick in picking things up, and have as good a knowledge of ‘affairs’ as the average junior Higher Division man. Whether they are capable of seeing through complex problems it is difficult to judge, for the period of war has not given much opportunity of trial in this respect, the main point having been to ‘carry on’ and to relegate problems to the happier days of peace. As a whole, women’s work is inferior to that of men, but against this has to be put the fact that at present they are in their infancy as far as public and office life is concerned, and have not that record of work behind them that pertains to their brothers. In order to give some idea of the problems with which they have to cope, the following instances are given.

There are various ladies serving in the finance branch who are charged with duties of an administrative character in regard to the finance of hospitals, National Health Insurance, etc. Another woman is engaged in coding and decoding telegrams. This entails much nicety of judgement, for whilst having to scrutinise them in order to avoid unnecessary extravagance, yet great care must be taken lest the omission of a word alters the sense of the message. The work in this section has been particularly arduous and has been carried out most satisfactorily.

Sea transport was in the hands of the War Office until the Ministry of Shipping took it over, and with it the staff that had been employed with the exception of two, one of whom was a woman. For some time after the transfer a considerable number of ‘ghosts’ remained, and questions of claims both for messing and passage had to be referred to the War Office; these were mostly dealt with by this woman. She also has considerable ability in dealing with figures, in this it might be stated that she is an exception to the general rule, being successful in dealing with adjustments with the Allies. The granting of import licences is another branch of work performed by a woman and for this she has to be cognisant of the various restrictions on certain goods, which restrictions are varied according to the countries concerned in the production. Another has the control of what may be described as a clearing house for current orthopaedic literature in order that different centres may be kept in touch with significant medical articles, foreign and British, and for this considerable editorial skill has been necessary.

Another was educated at Liverpool University and was a student of archaeology. She had done some work in connection with investigation of separation allowance claims and had also spent a short time in an office in the city. She was appointed at £2. 10s. a week as an inspector into wages complaints arising on War Office contracts. Her salary was soon raised to £3 a week, and later to £200 a year. For some time she was engaged on inspection duties, but after the transfer of a staff clerk in charge of the sub-section to other work she took charge and has carried out the work in a wholly satisfactory manner. The work involves the administration of the Fair Wages Clause in War Office contracts, and strikes and threatened strikes form a prominent feature of it. It is essential that the utmost tact and discretion should be used in dealings with the employers and Trade Union secretaries with whom negotiations take place, and this lady has throughout show herself competent.

Another came to us as temporary woman clerk at the ordinary rate for new entrants. She had some experience in business, partly in America. She soon attracted out attention by the ability she showed and was put in charge of a staff of six women engaged on general work in this branch; the chief part of her work consisted of the supervision of the clerical work on establishment questions affecting the Contracts Branch. For this work she was paid at the rate of £2 a week, and after a time at £2. 10s. When recruiting for the Army increased in severity she was transferred to the section dealing with the protection of Army Contractors’ labour, and was no longer a supervisor but was engaged on administrative work. A large number of appeals from contractors for the protection of essential men reached the Department, and it was her duty to take administrative action, referring to higher authority where she thought necessary. Her pay was soon increased to £3 a week. She has shown herself thoroughly competent to discharge her duties which involve speed, delegation of work, interviews with contractors and a full knowledge of the recruiting machinery. She is now a Junior Administrative Assistant, and one could not have wished for better work than she has done.

The approximate number of women employed is 4,648. In passing, a tribute should be paid to the excellent work done by the Girl Clerks who, under proper supervision and fresh from the discipline of school life, have proved themselves to be wonderfully quick and have taken an intelligent interest in their work. The best age for them to begin is thought to be about sixteen, their health being then more established and their brains more developed.

This finishes a brief outline of the assistance that has been rendered by women of high educational and technical qualifications, but whilst dwelling upon the help so willingly given by them, it must not be forgotten that during this long and strenuous war, their work could not have been satisfactorily accomplished, had it not been for the uncomplaining efforts of the hewers of wood and drawers of water in the shape of the Grade III clerks, whose work has been monotonous and hard, but who have carried on to the end.

*****

2. THE WAR WORK OF THE BLUE TRIANGLE

The war work of the Young Women’s Christian Association has not been confined to the Great European War, for it began with the Crimean War when the first Y.W.C.A. Hostel was opened for nurses returning from the Crimea.

Though the work for the girls in France began in 1917, whereas Huts and Canteens for other war-workers were in full swing by then, it is in this work that the public has always shown the greatest interest. Hundreds of Q.M.A.A.C.’s remember that during the Spring of 1918 it was the welcome of the Blue Triangle that helped them to fight the depression and tension that the German advance inevitably meant to the girls who were serving their country in the rear of its armies on the field. They eagerly acknowledge that it was the ‘homey-ness’ and brightness of the Blue Triangle Hut that helped to keep up their morale in those days of anxiety, terrible in England, but more desperate in France, where girls had hastily to retreat before the on-coming Germans, and take last messages for wife and sweetheart from men going up the line – so few to return. Over forty centres were opened in the base towns and camps in France, centres which the Women’s Commission appointed to inquire into the conduct of the Corps pronounced to be ‘valuable, and indeed, essential safeguards of the whole social position in France.’ Although eleven Huts or Clubs have been either destroyed by bombing (and it may be said that the girls’ courage during these attacks was beyond praise) or closed because the Units have been moved to another camp, over thirty are still running and are crowded by the girls and the men they invite as their guests.

Clubs for nurses and V.A.D.’s were the most extended of the war activities; in Cairo, Bombay, Basra and Amara (near Kut), these were opened chiefly owing to the inspiration and support of the Indian Y.W.C.A. They were immensely popular with the nurses, who very often faced great dangers; the Cairo Club, in particular, has welcomed many survivors of torpedoed ships. The care of refugees has been amongst the most useful war-work of the Association. Two London Clubs for Belgian girls were open early in the war, and the Blue Triangle is planning the establishment of hostels of Antwerp and Brussels to help them when they return to their country, often without trace of their families, and with no immediate work to keep them. In Vladivostock the Japanese National Secretary is caring for Russian refugees. For the many British refugees from Petrograd, the Y.W.C.A. opened a Hostel at 62, Gloucester Place, W., at the request of the late Ambassador. Within ten days of the signing of the Armistice, the Canadian Association sent an expert Immigration Secretary to confer with the authorities over the safe transit of 30,000 British wives of Canadian soldiers going over for the first time to make their homes in Canada, and she is now doing valuable work under the Government.

Throughout the war relatives of wounded soldiers found friendship and comfort in the Y.W.C.A. Hostels opened for them near the big military hospitals in London, Woolwich, Southampton and Salisbury Plain. Too often a mother or wife arrived only to find her son or husband at the point of death, and the sympathetic hospitality of the Blue Triangle was a godsend to the distracted women who had nowhere else to go. For many months the same spirit of helpfulness has been shown near the big London railway termini. Near Victoria the Victoria Hut has been the one great centre for all Service girls going to or coming from France on leave, who needed a bed for the night. Since the Armistice it is a regular thing for from thirty to forty girls to have shake-downs on chairs in the Y.W.C.A. hostels, thankful to have found a safe roof over their heads. Near Euston is a traveller’s hut, near Charing Cross the Trafalgar Square Inquiry Bureau. The Victoria Hut is also a canteen, serving 400 meals a day; typical of the 60 canteens opened during the war for war-workers.

Through these, through its 140 hostels, its many Holiday Camps, its 130 Patriotic Clubs, and its network of smaller clubs (part of the pre-war work), the Blue Triangle has been able to help every type of girl war-worker. The uniformed members of the Women’s Services, the land-girl, the munition girl in all her variety from the educated woman to the little worker of fourteen at her mechanical shell-filling, the porter, the business girl, the government clerk, the bus-conductor – special work has been done for every one of them, and the Association is finding its reward in the gratitude of the girls and the fear they are showing lest with the end of the war they should lose their Blue Triangle Hut. The Y.W.C.A. still has a big scheme. The Blue Triangle means comfort and comradeship, it means an honest attempt to meet the threefold need of every girl, physical, mental, spiritual. It means opportunities for education and for recreation. A soldier was heard to say:

“It’s like Heaven to be home in Blighty again, but there are little bits of Heaven in France – the Blue Triangle Huts.”

The Association hopes to have Hut-Clubs throughout the country to be as beloved in many crowded centres and small villages at home as they have been in France.

2. THE WAR WORK OF THE BLUE TRIANGLE

Young Women’s Christian Association

The war work of the Young Women’s Christian Association has not been confined to the Great European War, for it began with the Crimean War when the first Y.W.C.A. Hostel was opened for nurses returning from the Crimea.

Though the work for the girls in France began in 1917, whereas Huts and Canteens for other war-workers were in full swing by then, it is in this work that the public has always shown the greatest interest. Hundreds of Q.M.A.A.C.’s remember that during the Spring of 1918 it was the welcome of the Blue Triangle that helped them to fight the depression and tension that the German advance inevitably meant to the girls who were serving their country in the rear of its armies on the field. They eagerly acknowledge that it was the ‘homey-ness’ and brightness of the Blue Triangle Hut that helped to keep up their morale in those days of anxiety, terrible in England, but more desperate in France, where girls had hastily to retreat before the on-coming Germans, and take last messages for wife and sweetheart from men going up the line – so few to return. Over forty centres were opened in the base towns and camps in France, centres which the Women’s Commission appointed to inquire into the conduct of the Corps pronounced to be ‘valuable, and indeed, essential safeguards of the whole social position in France.’ Although eleven Huts or Clubs have been either destroyed by bombing (and it may be said that the girls’ courage during these attacks was beyond praise) or closed because the Units have been moved to another camp, over thirty are still running and are crowded by the girls and the men they invite as their guests.

Clubs for nurses and V.A.D.’s were the most extended of the war activities; in Cairo, Bombay, Basra and Amara (near Kut), these were opened chiefly owing to the inspiration and support of the Indian Y.W.C.A. They were immensely popular with the nurses, who very often faced great dangers; the Cairo Club, in particular, has welcomed many survivors of torpedoed ships. The care of refugees has been amongst the most useful war-work of the Association. Two London Clubs for Belgian girls were open early in the war, and the Blue Triangle is planning the establishment of hostels of Antwerp and Brussels to help them when they return to their country, often without trace of their families, and with no immediate work to keep them. In Vladivostock the Japanese National Secretary is caring for Russian refugees. For the many British refugees from Petrograd, the Y.W.C.A. opened a Hostel at 62, Gloucester Place, W., at the request of the late Ambassador. Within ten days of the signing of the Armistice, the Canadian Association sent an expert Immigration Secretary to confer with the authorities over the safe transit of 30,000 British wives of Canadian soldiers going over for the first time to make their homes in Canada, and she is now doing valuable work under the Government.

Throughout the war relatives of wounded soldiers found friendship and comfort in the Y.W.C.A. Hostels opened for them near the big military hospitals in London, Woolwich, Southampton and Salisbury Plain. Too often a mother or wife arrived only to find her son or husband at the point of death, and the sympathetic hospitality of the Blue Triangle was a godsend to the distracted women who had nowhere else to go. For many months the same spirit of helpfulness has been shown near the big London railway termini. Near Victoria the Victoria Hut has been the one great centre for all Service girls going to or coming from France on leave, who needed a bed for the night. Since the Armistice it is a regular thing for from thirty to forty girls to have shake-downs on chairs in the Y.W.C.A. hostels, thankful to have found a safe roof over their heads. Near Euston is a traveller’s hut, near Charing Cross the Trafalgar Square Inquiry Bureau. The Victoria Hut is also a canteen, serving 400 meals a day; typical of the 60 canteens opened during the war for war-workers.

Through these, through its 140 hostels, its many Holiday Camps, its 130 Patriotic Clubs, and its network of smaller clubs (part of the pre-war work), the Blue Triangle has been able to help every type of girl war-worker. The uniformed members of the Women’s Services, the land-girl, the munition girl in all her variety from the educated woman to the little worker of fourteen at her mechanical shell-filling, the porter, the business girl, the government clerk, the bus-conductor – special work has been done for every one of them, and the Association is finding its reward in the gratitude of the girls and the fear they are showing lest with the end of the war they should lose their Blue Triangle Hut. The Y.W.C.A. still has a big scheme. The Blue Triangle means comfort and comradeship, it means an honest attempt to meet the threefold need of every girl, physical, mental, spiritual. It means opportunities for education and for recreation. A soldier was heard to say:

“It’s like Heaven to be home in Blighty again, but there are little bits of Heaven in France – the Blue Triangle Huts.”

The Association hopes to have Hut-Clubs throughout the country to be as beloved in many crowded centres and small villages at home as they have been in France.

*****

3. WOMEN IN THE R.A.S.C.

The foundations of the Women’s Forage Corps, R.A.S.C. [Royal Army Service Corps], were laid in 1915, but the Corps did not come into being as a whole till March 1917. It came under the administration of Brigadier-General H. Godfrey Morgan, C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O., and Mrs. Stewart was appointed Superintendent. The development of the Corps was a more formidable undertaking than the organization of any of the other Women’s Corps, owing to the fact that the girls have been scattered all over the country, working side by side with the men. Difficulties of discipline and so forth were rendered greater by the essentially peripatetic nature of the work, but a high morale has been excellently maintained, and the women have won for themselves the respect and friendship of the country people, who at first regarded them with very mixed feelings.

The numbers of the W.F.C. have reached about 6,000 and the organization is as follows:

First Mrs. [Athol] Stewart, Superintendent of Women, under her are the Area Inspectors of Women, scattered over the country. Beneath their control, work Assistant Superintendents and Deputy Superintendents who are classed as first grade officials. In the second grade come the Forwarding Supervisors, and the Supervisors of Women Labour. The rank and file of the Corps are known as Industrial Members; these earn on an average 26s. to 30s. a week. They work in gangs of six, headed by a Gang Supervisor who is promoted on the analogy of N.C.O.’s from the ranks of the Industrial Members. The work of the women is concerned exclusively with forage, but varies considerably. Some help to bale hay, working with a steam baler, others act as transport drivers in charge of the horses; these are responsible for the carriage of the hay from the stacks to the railway stations. The forwarding supervisors are responsible for the checking of the bales of hay on their arrival at the stations, for the supervision of the loading of hay into the trucks, of the correct tonnage, the sheeting of the trucks and so forth. The Section Clerks are occupied in the purely clerical work of the Section; these also move about the country following the baler. This wandering mode of work has made the provision of adequate housing for the girls very difficult. As a rule they are billeted in neighbouring cottages, and the arrangements as a whole are under the charge of a Deputy-Assistant-Supervisor, who controls two sections of twenty-four girls each. The W.F.C. members draw Army rations, and sometimes a gang of six girls will be provided with a caravan and a cook, with whose aid they enjoy a gipsy life. The caravans are never used for sleeping purposes, only as a central mess.

The uniform of the W.F.C. consists for industrial members of black boots and gaiters, dark green breeches, khaki overalls, dark green jerseys and dark green hats. They bear F.C. in brass on their shoulder straps, and the kit is completed by a khaki overcoat and haversack. The officials wear a khaki tunic and skirt, with badges of rank on the shoulders, dark green hats, and their badge of F.C. is in bronze. The F.C. of all badges is enclosed in the R.A.S.C. eight-pointed star, and the members are deservedly proud of their link with the Army. The physical improvement shown by the W.F.C. recruits, most of whom were drawn from the domestic servant class, is surprising. Among the transport members, there are several of independent means, Irish girls with horses of their own.

There are other interesting branches of forage work such as chaffing, wire-stretching, tarpaulin sheet mending, sack making and mending, all of which are carried on at various stores in the different areas. It may be mentioned that in pre-war times tarpaulin sheet mending was one of the many forms of employment considered to be essentially a man’s work, but the women have proved themselves thoroughly capable in this direction and maintained a high standard of proficiency.

All classes, officials and members have worked loyally very often under trying conditions, inclement weather and many other disadvantages. The gipsy life, after a time, is inclined to become monotonous, and the lack of amusements in remote villages after the day’s work is done is felt by girls who have become used to the attractions of the town. The Forage Corps girl in her workmanlike uniform has been seen very rarely in the Metropolis; the conditions of her work have not permitted her to take a conspicuous part in any of the functions which have been organized to show the general public a representative body of women workers. Rich and poor, the Forage Corps has the satisfaction of knowing that they replaced a man, and that without them the extremely essential work of forage supply, both for the forces at home and the armies overseas, could not have been carried on.

*****

4. UNDER THE GREENWOOD TREE

*****

Back to Top

3. WOMEN IN THE R.A.S.C.

Women’s Forage Corps

The foundations of the Women’s Forage Corps, R.A.S.C. [Royal Army Service Corps], were laid in 1915, but the Corps did not come into being as a whole till March 1917. It came under the administration of Brigadier-General H. Godfrey Morgan, C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O., and Mrs. Stewart was appointed Superintendent. The development of the Corps was a more formidable undertaking than the organization of any of the other Women’s Corps, owing to the fact that the girls have been scattered all over the country, working side by side with the men. Difficulties of discipline and so forth were rendered greater by the essentially peripatetic nature of the work, but a high morale has been excellently maintained, and the women have won for themselves the respect and friendship of the country people, who at first regarded them with very mixed feelings.

The numbers of the W.F.C. have reached about 6,000 and the organization is as follows:

First Mrs. [Athol] Stewart, Superintendent of Women, under her are the Area Inspectors of Women, scattered over the country. Beneath their control, work Assistant Superintendents and Deputy Superintendents who are classed as first grade officials. In the second grade come the Forwarding Supervisors, and the Supervisors of Women Labour. The rank and file of the Corps are known as Industrial Members; these earn on an average 26s. to 30s. a week. They work in gangs of six, headed by a Gang Supervisor who is promoted on the analogy of N.C.O.’s from the ranks of the Industrial Members. The work of the women is concerned exclusively with forage, but varies considerably. Some help to bale hay, working with a steam baler, others act as transport drivers in charge of the horses; these are responsible for the carriage of the hay from the stacks to the railway stations. The forwarding supervisors are responsible for the checking of the bales of hay on their arrival at the stations, for the supervision of the loading of hay into the trucks, of the correct tonnage, the sheeting of the trucks and so forth. The Section Clerks are occupied in the purely clerical work of the Section; these also move about the country following the baler. This wandering mode of work has made the provision of adequate housing for the girls very difficult. As a rule they are billeted in neighbouring cottages, and the arrangements as a whole are under the charge of a Deputy-Assistant-Supervisor, who controls two sections of twenty-four girls each. The W.F.C. members draw Army rations, and sometimes a gang of six girls will be provided with a caravan and a cook, with whose aid they enjoy a gipsy life. The caravans are never used for sleeping purposes, only as a central mess.

The uniform of the W.F.C. consists for industrial members of black boots and gaiters, dark green breeches, khaki overalls, dark green jerseys and dark green hats. They bear F.C. in brass on their shoulder straps, and the kit is completed by a khaki overcoat and haversack. The officials wear a khaki tunic and skirt, with badges of rank on the shoulders, dark green hats, and their badge of F.C. is in bronze. The F.C. of all badges is enclosed in the R.A.S.C. eight-pointed star, and the members are deservedly proud of their link with the Army. The physical improvement shown by the W.F.C. recruits, most of whom were drawn from the domestic servant class, is surprising. Among the transport members, there are several of independent means, Irish girls with horses of their own.

There are other interesting branches of forage work such as chaffing, wire-stretching, tarpaulin sheet mending, sack making and mending, all of which are carried on at various stores in the different areas. It may be mentioned that in pre-war times tarpaulin sheet mending was one of the many forms of employment considered to be essentially a man’s work, but the women have proved themselves thoroughly capable in this direction and maintained a high standard of proficiency.

All classes, officials and members have worked loyally very often under trying conditions, inclement weather and many other disadvantages. The gipsy life, after a time, is inclined to become monotonous, and the lack of amusements in remote villages after the day’s work is done is felt by girls who have become used to the attractions of the town. The Forage Corps girl in her workmanlike uniform has been seen very rarely in the Metropolis; the conditions of her work have not permitted her to take a conspicuous part in any of the functions which have been organized to show the general public a representative body of women workers. Rich and poor, the Forage Corps has the satisfaction of knowing that they replaced a man, and that without them the extremely essential work of forage supply, both for the forces at home and the armies overseas, could not have been carried on.

4. UNDER THE GREENWOOD TREE

Women’s Forestry Service

The Women’s Forestry Service was started by Miss Rosamund Crowdy, as one of the three sections of the Land Army. While the Land Army is, as a whole, under the Board of Agriculture, the Women’s Forestry Service is directly under the Board of Trade. The Land Army and the Forestry Corps have always worked in close co-operation. The former has done all the recruiting work for the latter, and selected and passed all candidates for Forestry work, while the county organizers of the Land Army have worked for the Forestry scheme.

The Forestry Service started with two camps for ‘cutters,’ each numbering about twenty girls, and one camp for timber ‘measurers’ of twenty-five. Of course, before this definite training scheme was organized, quite a number of women had been employed in the cutting and measuring of timber. These were, however, local women, without uniform or organization. The first measurers’ camp was under canvas at Penn, in Buckinghamshire, but in September, 1917, it was moved into wooden huts at Halton, Wendover, in the same county. Huts have been found by far the most satisfactory way of housing the workers, as the tents seldom withstood the rains of an English summer; in Devonshire, last year, a whole camp of foresters was completely flooded out.

About 370 women have passed through the measurers’ training camp since its inauguration. Of these, only 5 per cent have withdrawn before completing their contracts. Timber measuring, which includes a knowledge of felling, marking, and so on, is a skilled trade, and the girls who took it up were chiefly drawn from the ranks of school teachers, superior bank clerks and so forth. After their training is completed they are frequently sent out as forewomen in charge of timber gangs consisting of twenty to thirty cutters. Measurers have also been put practically in charge of saw mills, work involving the keeping of accounts, and entailing great accuracy, rather than physical strength. The course of training at Wendover is very complete, and requires both a theoretical and practical knowledge of forestry.

The work of ‘cutters’ is, of course, less skilled, and calls for a physical strength above the average. This fact accounts for the rejection on medical grounds of 18 per cent of the cutters out of a total of 1,800. Those who can endure are picked girls, and it is these who form the bulk of the Forestry Service. The two inaugural training camps for cutters, started at Newstead in Nottinghamshire and Burnham in Norfolk, were closed down in a month, as they were found unnecessary. The girls now go straight to work, and become in two or three days sufficiently practised for the easier jobs in forestry. In a few months they are usually capable of the actual felling of trees. The cutters are hired to private employers, or work in gangs under their divisional officers.

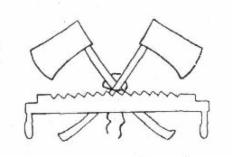

The uniform is the same as that of the Land Army, boots, breeches, white overalls and slouch hat, but the Foresters bear on their armlets and hat a distinctive and highly artistic badge. This was designed by one of the corps, herself an artist, and consists, for the measurers, of a tree embroidered in green silk on a khaki background, surrounded by the letters W. F. S. The cutters have, instead, two crossed woodman’s axes, and cross saw, while the letters L. A. T. S. are added. The pay has been fixed by the Government at a minimum of 35s. per week for measurers (with uniform and travelling expenses) rising after six months by monthly increments of 2s. 6d. The cutters get 22s. 6d. a week, unless they are paid by piece rates. The piece rate system is the one recommended to employers by the Forestry Service, and the girls usually earn more that way.

The Forestry Service started with two camps for ‘cutters,’ each numbering about twenty girls, and one camp for timber ‘measurers’ of twenty-five. Of course, before this definite training scheme was organized, quite a number of women had been employed in the cutting and measuring of timber. These were, however, local women, without uniform or organization. The first measurers’ camp was under canvas at Penn, in Buckinghamshire, but in September, 1917, it was moved into wooden huts at Halton, Wendover, in the same county. Huts have been found by far the most satisfactory way of housing the workers, as the tents seldom withstood the rains of an English summer; in Devonshire, last year, a whole camp of foresters was completely flooded out.

About 370 women have passed through the measurers’ training camp since its inauguration. Of these, only 5 per cent have withdrawn before completing their contracts. Timber measuring, which includes a knowledge of felling, marking, and so on, is a skilled trade, and the girls who took it up were chiefly drawn from the ranks of school teachers, superior bank clerks and so forth. After their training is completed they are frequently sent out as forewomen in charge of timber gangs consisting of twenty to thirty cutters. Measurers have also been put practically in charge of saw mills, work involving the keeping of accounts, and entailing great accuracy, rather than physical strength. The course of training at Wendover is very complete, and requires both a theoretical and practical knowledge of forestry.

The work of ‘cutters’ is, of course, less skilled, and calls for a physical strength above the average. This fact accounts for the rejection on medical grounds of 18 per cent of the cutters out of a total of 1,800. Those who can endure are picked girls, and it is these who form the bulk of the Forestry Service. The two inaugural training camps for cutters, started at Newstead in Nottinghamshire and Burnham in Norfolk, were closed down in a month, as they were found unnecessary. The girls now go straight to work, and become in two or three days sufficiently practised for the easier jobs in forestry. In a few months they are usually capable of the actual felling of trees. The cutters are hired to private employers, or work in gangs under their divisional officers.

The uniform is the same as that of the Land Army, boots, breeches, white overalls and slouch hat, but the Foresters bear on their armlets and hat a distinctive and highly artistic badge. This was designed by one of the corps, herself an artist, and consists, for the measurers, of a tree embroidered in green silk on a khaki background, surrounded by the letters W. F. S. The cutters have, instead, two crossed woodman’s axes, and cross saw, while the letters L. A. T. S. are added. The pay has been fixed by the Government at a minimum of 35s. per week for measurers (with uniform and travelling expenses) rising after six months by monthly increments of 2s. 6d. The cutters get 22s. 6d. a week, unless they are paid by piece rates. The piece rate system is the one recommended to employers by the Forestry Service, and the girls usually earn more that way.

*****

Back to Top